SPONSOR:Â Esports Entertainment Group (GMBL:OTCQB) Agoracom HUB / Fast Profile /

LATEST NEWS:Â Esports Entertainment Group Secures $2M Financing

SPONSOR:Â Esports Entertainment Group (GMBL:OTCQB) Agoracom HUB / Fast Profile /

LATEST NEWS:Â Esports Entertainment Group Secures $2M Financing

Graphene is an emerging market opportunity with many potential applications. The challenge for a new supplier like ZEN is to define the priority market segments offering the best value creation potential. ZEN is tackling this challenge by working in close collaboration with researchers both in industry and in academia. From the work done by the ZEN team over just the past 6 months, the Company is now actively collaborating with 22 industrial end users and 10 Canadian universities. ZEN is also receiving significant interest from multiple Canadian government agencies who have already directly contributed over $2 million to ZEN’s graphene research and development work.

Dr. Francis Dubé Co-CEO commented, “Our model of bringing together end-users with specific graphene-related opportunities and researchers from top Canadian Universities to provide industry specific graphene solutions is proving to be attractive to all parties. We are creating win-win-win scenarios for everyone involved as we help solve industry challenges in delivering the power of graphene to end-users. Our work is also bringing leading edge research projects to Canadian academia and creating demand for our graphene products while developing potentially valuable intellectual property (IP) protected inventions. The work being done across the country has the potential to make Canada a leader in the emerging clean technology-oriented graphene industry.”

ZEN’s graphene solutions and the potential economic benefit that they can bring to the Canadian economy has attracted the attention of several government agencies that are supporting innovation, sustainability and new clean technology. The Company will continue to work with the government program coordinators for the opportunities that ZEN’s unique Albany Graphite product offers for innovative nano-materials applications. This effort is led by ZEN’s Ottawa-based Outreach Program Coordinator, Monique Manaigre.

The market development work is being led by the Company’s Head of Sales, Phil Chataigneau along with Research Catalyst, Colin van der Kuur. Their combined efforts have led to the development of the 5 most significant potential graphene market verticals:

Aerospace Applications:

Graphene light-weighting, hydrogen applications, Lightning strike protection, composite enhancement, solid state heat sinks, solid state wiring, leading edge/wing de-icing, ceramic armour, radar/sonar absorption, technical/smart fabrics, personal body armour, Graphene Oxide (GO) in jet fuel, lighter cargo containers.

Biomedical Applications:

Oncology treatment using Graphene Quantum Dots (GQD) to deliver targeted therapies.

Diabetes, other standard diagnostic testing with Functionalized GO sensors.

Water Treatment:

Graphene based desalination membranes and other water purification products.

Transportation:

Applications with auto makers and resin manufacturers for: Heat Sinks & Light-weighting, Graphene wires for electric motors, graphene 3-d printing apps to deliver weight savings, (GO) Fuel Additives (Diesel & Jet Fuel), Hydrogen Economy: Fuel Cells, Electrolysis Units, Next-Generation Fuel Cells with graphene 3-D printed circuits and graphene plates.

Civil Engineering:

Graphene additive in cement/concrete.

Graphene in roads/surfacing products.

In recognition of the excellent progress made by the Company’s market development team over the past six months, the Board of Directors has approved the grant of 50,000 incentive stock options grant to each of these three individuals. These options will be priced at $0.40 per share. One-third of the options vested on the date of their grant, one-third of the options will vest six months following the date of grant and the balance will vest on the one-year anniversary of the date of grant. The options have a term of two years and are subject in all respects to the terms of the Company’s incentive stock option plan and the policies of the TSX Venture Exchange.

For further information:

Dr. Francis Dubé, Co-CEO & Head of Business Development and Technology

Tel: +1 (289) 821-2820

Email: [email protected]

About Zenyatta

Zenyatta’s Albany Graphite Project hosts a large and unique quality deposit of highly crystalline graphite. Independent labs in Japan, UK, Israel, USA and Canada have demonstrated that Zenyatta’s Albany Graphite/Naturally PureTM easily converts (exfoliates) to graphene using a variety of simple mechanical and chemical methods. The deposit is located in northern Ontario just 30km north of the Trans-Canada Highway, near the communities of Constance Lake First Nation and Hearst. Important nearby infrastructure include hydro-power, natural gas pipeline, a rail line 50 km away and an all-weather road just 10 km from the deposit.

To find out more on Zenyatta Ventures Ltd., please visit our website at www.zenyatta.ca. A copy of this press release and all material documents with respect of the Company may be obtained on Zenyatta’s SEDAR profile at www.sedar.ca.

By Dr. Kiran Garimella

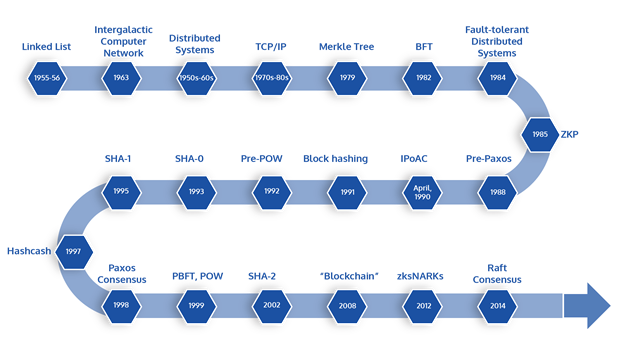

In parts 1-3, we briefly touched on some of the historical foundations of blockchains from computer science and mathematics, including their sub-topics such as distributed systems and cryptography. Specific topics in either of these categories were consensus mechanisms, fault-tolerance, scaling, zero-knowledge proofs, etc.

Obviously, this brief series doesn’t do justice. The history of computing and mathematics is rich, with many interconnections and dependencies. The goal of this series was to provide just enough to make the point that the technologies that power blockchain (whether public or private) were built on a well-established foundation of various topics with contributions from real scientists in both industry and academia. The graphic below depicts the broad brush-strokes of development, clearly showing how current blockchain technologies are based on a wide spectrum of historical developments.

Technologies of Blockchain – Historical Timeline

Conclusion

As you can see, a tremendous amount of development that took place for almost half a century made the modern blockchain possible. Bringing these technologies together—almost all of them based not on just techniques but deep mathematical foundations—into a cohesive whole in the form of a bitcoin application was no doubt a tremendous achievement in itself.

Moving forward, we need to keep in mind the initial motivation for each of these technologies, their strengths, their limitations, and determine how to create different architectures based on business needs. A good example of this is to relax the requirements of anonymity, strengthen safety, incorporate recourse, improve security, and incorporate the enormous complexity of regulatory compliance in securities transactions. Making such trade-offs doesn’t detract from the need for public, decentralized blockchains. On the contrary, this strengthens the use of the blockchain technology ‘horizontally’ across many industries and use cases.

In the near future, we expect to see some innovation in blockchains to improve performance and scalability, which is a special challenge for public blockchains. Along the same lines, there will be new consensus mechanisms going mainstream (such as proof-of-stake). For consensus and validation, blockchain researchers are investigating efficient implementation of zero-knowledge proofs and specific variants such as zkSNARKs.

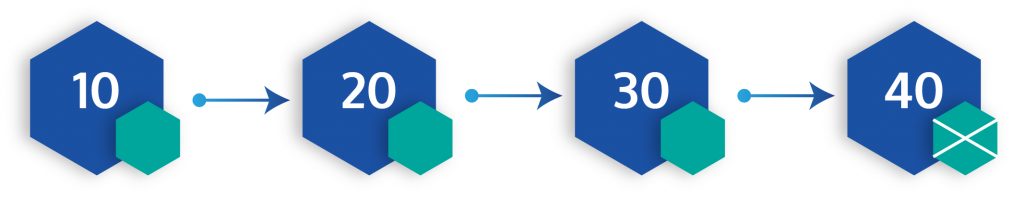

In Part 2, we saw how a simple concept of a linked list can morph into complex, distributed systems. Obviously, this is a simple, conceptual evolution leading up to blockchain, but it’s not the only way distributed systems can arise. Distributed systems need coordination, fault tolerance, consensus, and several layers of technology management (in the sense of systems and protocols).

Distributed systems also have a number of other complex issues. When the nodes in a distributed system are also decentralized (from the perspective of ownership and control), security becomes essential. That’s where complex cryptographic mechanisms come into play. The huge volume of transactions makes it necessary to address performance of any shared or replicated data, thus paving the way to notions of scaling, sharding, and verification of distributed data to ensure that it did not get out of sync or get compromised. In this segment, we will see that these ideas are not new; they were known and have been working on for several decades.

Cryptography

One important requirement in distributed systems is the security of data and participants. This motivates the introduction of cryptographic techniques. Ralph Merkle, for example, introduced in 1979 the concept of a binary tree of hashes (now known as a Merkle tree). Cryptographic hashing of blocks was implemented in 1991 by Stuart Haber & W. Scott Stornetta. In 1992, they incorporated Merkle trees into their scheme for efficiency.

The hashing functions are well-researched, standard techniques that provide the foundation for much of modern cryptography, including the well-known SSL certificates and the https protocol. Merkle’s hash function, now known as the Merkle-Damgard construction, is used in SHA-1 and SHA-2. Hashcash uses SHA-1 (original SHA-0 in 1993, SHA-1 in 1995), now using the more secure SHA-2 (which actually consists of SHA-256 and SHA-512). The more secure SHA-3 is the next upgrade.

Partitioning, Scaling, Replicating, and Sharding

Since the core of a blockchain is the database in the form of a distributed ledger, the question of how to deal with the rapidly growing size of the database becomes increasingly urgent. Partitioning, replicating, scaling, and sharding are all closely related concepts. These techniques, historically used in enterprise systems, are now being employed in blockchains to address performance limitations.

As with all things blockchain, these are not new concepts either, since large companies have been struggling with these issues for many decades, though not from a blockchain perspective. The intuitively obvious solution for a growing database is to split it up into pieces and store the pieces separately. Underlying this seemingly simple solution lies a number of technical challenges, such as how would the application layer know in which “piece†any particular data record would be found, how to manage queries across multiple partitions of the data, etc. While these scalability problems are tractable in enterprise systems or in ecosystems that have known and permitted participants (i.e., the equivalent of permissioned blockchains), it gets trickier in public blockchains. The permutations for malicious strategies seem endless and practically impossible to enumerate in advance. The need to preserve reasonable anonymity also increases the complexity of robust solutions.

Verification and Validation

Zero-knowledge proofs (ZKP) are techniques to prove (to another party, called the verifier) that the prover knows something without the prover having to disclose what it is that the prover knows. (This sounds magical, but there are many simple examples to show how this is possible that I’ll cover in a later post.) ZKP was first described in a paper, “The Knowledge Complexity of Interactive Proof-Systems†in 1985 by Shafi Goldwasser, Silvio Micali, and Charles Rackoff (apparently, it was developed much earlier in 1982 but not published until 1985). Zcash, a bitcoin-based cryptocurrency, uses ZKPs (or variants called zkSNARKs, first introduced in 2012 by four researchers) to ensure validity of transactions without revealing any information about the sender, receiver, or the amount itself.

Some of these proofs and indeed the transactions themselves could be implemented by automated code, popularly known as smart contracts. These were first conceived by Nick Szabo in 1996. Despite the name, it is debatable if these automated pieces of code can be said to be smart given the relatively advanced current state of artificial intelligence. Similarly, smart contracts are not quite contracts in the legal sense. A credit card transaction, for example, incorporates a tremendous amount of computation that includes checking for balances, holds, fraud, unusual spending patterns, etc., with service-level agreements and contractual bindings between various parties in the complex web of modern financial transactions, but we don’t usually call this a ‘smart contract’. In comparison, even the current ‘smart contracts’ are fairly simplistic.

Read Part 1: The Foundations and Part 2: Distributed Systems

Source: https://www.koreconx.com/2018/11/28/technologies-blockchain-part-3-cryptography-scaling-consensus/

Blockchain is not just a single technology but a package of a number of technologies and techniques. The rich lexicon in the blockchain includes terms such as Merkle trees, sharding, state machine replication, fault tolerance, cryptographic hashing, zero-knowledge proofs, zkSNARKS, and other exotic terms.

In this four-part series, we will provide a very high-level overview of each of the main components of technology. In reality, the number of technologies, variations, configurations, and considerations of trade-offs are numerous. Each piece in this puzzle was motivated by certain business requirements and technical considerations.

In this first part, we look at the origins of the ‘chain’ and the most important technological advancement that makes blockchain (and all e-commerce) possible, i.e., the Internet.

While there have been genuine innovations within the last decade, blockchain’s underlying technologies are mostly quite old (in computer science time scale). Let us unpack a typical blockchain to trace out the origins of the constituent technologies. In this short post, I’ll only point to a very small (some may say, infinitesimally small) subset of the historical origin of technologies that make the modern blockchain possible. I’ll make no attempt to trace the development of these concepts from origin to the present time (that would fill up several books). The fact that blockchain’s technologies have a long and respectable history should help us gain confidence that blockchain, as a technology, is not some fly-by-night, newfangled idea cooked up by the crypto fandom.

What is less certain and much more controversial is the economic justification for blockchain (or at least some types of blockchain), ranging from the unrealistic expectation that it is a panacea for all of humankind’s ills (most optimistically, for social and economic inequities), to the total and premature dismissal of blockchain in its entirety.

The Beginnings

At the conceptual heart of blockchain is the ‘chain’. By definition, the links of the chain are, well, linked. It’s a list of data elements or packets of information (in blockchain, these are called ‘blocks’) that are linked. A blockchain is, therefore, a type of linked list.

The concept of a linked list was defined by pioneers of computer science and artificial intelligence, Alan Newell, Cliff Shaw, and Herbert Simon, way back in 1955-56.

In the early days of computer science, data and processing power lived on individual computers. Soon, people wanted these computers to ‘talk’ to each other. The grand idea of an Intergalactic Computer Network was put forth by J. C. R. Licklider as early as 1963. Unfortunately, even after half a century of rapid development, we have achieved only a planetary-wide Internet so far. An ‘intergalactic’ network is still a few years away!*

These ideas and the need to connect dispersed computers gave rise to wide-scale distributed systems in the 1960s-70s, with the advent of ARPANET and Ethernet. Technically, these linked computers are not necessarily treated in the same way as a traditional linked list that lived on one computer, but the conceptual idea is similar. When data and computational power get dispersed, layers of management, coordination, and security become increasingly important.

Blockchain would not exist without the Internet, which itself would not exist without TCP/IP, developed by Bob Kahn and Vint Cerf in the 1970s and ‘80s. Along the way, some scientists managed to have some fun too. They carried out an April Fools prank in 1990 by issuing an RFC (1149) for IPoAC protocol (IP over Avian Carriers, i.e., carrier pigeons). The punch line was delivered in April 2001 when a Linux user group implemented CPIP (Carrier Pigeon Internet Protocol) by sending nine data packets over three miles using carrier pigeons. They reported packet loss of 55%. A joke that takes a decade to pull off is practically Saturday night live comedy in Internet time scale!

In part 2, we will see how the extension of the concept of linked list on the Internet leads to distributed systems, the attending challenges, and their solutions.

Source: https://www.koreconx.com/2018/11/14/technologies-blockchain-part-1-foundations/

FULL DISCLOSURE: Gratomic is an advertising client of AGORA Internet Relations Corp.

FULL DISCLOSURE: Labrador Gold is an advertising client of AGORA Internet Relations Corp.