SPONSOR: Lomiko Metals LMR:TSX-V – A Canadian exploration-stage

company discovered high-grade graphite at its La Loutre Property in

Quebec and is working toward a Pre-Economic Assessment (PEA) that will

increase its current indicated resource of 4.1 Mt of 6.5% Cg to over 10

Mt of 10%+ Cg through a 21 hole program at the Refractory Zone. Click Here For More Information

In 2010 the US Department of Energy’s Critical Materials Strategy included lithium as one of 14 elements expected to play a vital role in America’s clean energy economy.

Lithium is also among 23 critical metals

President Trump has deemed critical to national security; in 2017 Trump

signed a bill that would encourage the exploration and development of

new US sources of these metals.

According to the US Geological Survey, the United States last year imported around half of 48 minerals and 100% of 18 minerals.

According to Benchmark Mineral Intelligence the US only produces 1% of global lithium supply and 7% of refined lithium chemicals, versus China’s 51%.

A Tesla executive earlier in the year said

the company is worried about a shortage of lithium. The number of EVs

are expected to multiply in coming years, but they can only progress as

fast as the lithium-ion batteries can get built that go into them. Tesla

CEO Elon Musk said, in June of 2019, that in order to ensure Tesla has

enough batteries to expand its product line Tesla might get into mining

lithium for itself.

The world’s leading lithium battery

companies in 2016 produced 29 gigawatt-hours (GWh) of batteries. By 2028

forecasted production is expected to hit 1,049 GWh, an increase of

3,516%!

Consider that in 2018, China sold 1.182

million NEVs (new energy vehicles including electrics and hybrids),

520,000 or 78% more than in 2017.

As China’s mark on the lithium market becomes more pronounced, growth in the sale of lithium end products is taking off.

According to Adamas Intelligence, in

February 2019, 75% more lithium carbonate was deployed for batteries in

electric and hybrid passenger vehicles compared to February, 2018.

At Ahead of the Herd we know that the

lithium market, in a few short years, is going to be in deficit as

troubles ramping up production meet a mounting wall of demand. It’s

obvious Tesla’s CEO understands that in order to grow his company he has

to have a secure supply of lithium.

Lithium price explainer

Before we go any further let’s take a

look at the different prices of lithium; with 11 lithium products

currently being assessed, it can get confusing. While the mineral used

to be priced in long-term contracts like uranium, recently there has

been a push by end-users, particularly automotive manufacturers, for

more price transparency.

As we can see in the price chart below,

short-term the lithium bears have the upper hand, with lithium prices

falling in China and South America, along with the price of spodumene

concentrate in Australia.

How are prices determined? There are three

factors Benchmark Mineral Intelligence uses to set the industry standard

reference prices: quality/ grade of lithium, shipping costs/ volumes,

and the reliability of information given.

The grade and level of impurities affect the

price a miner receives, for the lithium to be processed into spodumene

concentrate, lithium carbonate or lithium hydroxide. Often the product

is refined into the exact specifications required by the end-user.

Currently there are six prices of lithium carbonate, four for lithium hydroxide and one spodumene concentrate price:

- Benchmark Minerals, Lithium Carbonate, 99%, FOB South America, USD/tonne

- Benchmark Minerals, Lithium Carbonate, 99%, CIF North America, USD/tonne

- Benchmark Minerals, Lithium Carbonate, 99.2%, CIF Europe, USD/tonne

- Benchmark Minerals, Lithium Carbonate, 99.2%, CIF Asia, USD/tonne

- Benchmark Minerals, Lithium Carbonate, Battery Grade, 99.5%, EXW China, RMB/tonne

- Benchmark Minerals, Lithium Carbonate, Technical Grade, 99%, EXW China, RMD/tonne

- Benchmark Minerals, Lithium Hydroxide, 55%, FOB North America, USD/tonne

- Benchmark Minerals, Lithium Hydroxide, 56.5%, CIF Asia, USD/tonne

- Benchmark Minerals, Lithium Hydroxide, 55%, CIF Europe, USD/tonne

- Benchmark Minerals, Lithium Hydroxide, 56.5%, EXW China, RMB/tonne

- Benchmark Minerals, Spodumene Concentrate, 6%, FOB Australia

In July Benchmark Intelligence published an update on lithium prices titled

‘Lithium’s price paradox’. Current prices are a paradox because lithium

investors are making decisions based on short-term supply versus

long-term market fundamentals.

Indeed there has been an influx of

new supply entering the market. Last year four hard-rock (spodumene)

operations in Australia started production. The number of active lithium

mines in Australia grew from one in 2016 to nine by year-end 2018.

A total of five new lithium conversion

plants (plants that convert lithium carbonate to lithium hydroxide) have

come into production and another three have expanded their output to

meet market demand.

What is promised in not always delivered

Past success however is not necessarily

indicative of the future. We know that between 2012 and 2016, major

lithium miners planned to produce an extra 200,000 tonnes of new supply.

But when 2016 rolled around, under 50,000 new tonnes came online, due

to technical problems.

According to Benchmark’s research, only

three plants in China have reached production and full capacity. Beyond

the Tier 1 producers shown in green in the table below, just two –

General Lithium (16,000t) and Jiangte Motor (25,000t) – managed to meet

production targets of 41,500t. That means only 87,000t of new Chinese

capacity has hit the market since 2016, of a planned 481,500t:

The false narrative which emerged from

these expansions and spilled over into 2019 was that the industry was

awash with battery-grade lithium chemicals, sufficient to support rapid

electrification over coming years.

Benchmark notes more major expansions

outside China are planned this year but the timelines for completion are

vague and delays are expected; thus the myth of over-supply in the face

of exponentially high future demand for lithium. The research firm

predicts supply would have to increase at a compound annual growth rate

(CAGR) of 19% over the next six years to meet 2025 demand. From 2015 to

2018 it grew at just 11%:

While the supply response has addressed

the relatively minor growth of today, it is still far from meeting the

needs of tomorrow’s EV expansions.

Spectators that flocked to the market in

2016 on the promise of an EV super-cycle have left before the warm up,

let alone the main event.

While a downturn in prices has reflected

a necessary correction towards near-term market fundamentals, it fails

to represent the increasing possibility of another major deficit in the

market by the early-2020s, creating a deceptive narrative in both share

prices and surrounding markets.

Another important point is that, despite the

hundreds of thousands of tonnes more lithium chemical production

capacity, only a small percentage will make it into lithium-ion

batteries. Why?

Lithium carbonate contained in brines must

have contaminants removed before it can be considered battery-grade

quality; the process of removing impurities can be expensive.

Technical-grade lithium used in applications

other than for EV batteries such as glass and ceramics, is cheaper than

battery-grade material, but it has to have low concentrations of iron

to be upgraded. There may also be teething problems at new operations.

Says Benchmark:

As with any new lithium chemical

production, only a proportion of this material will likely be sold into

the battery sector from the outset. Even leading producers have problems

meeting specs in the initial stages of production.

Both lithium carbonate and hydroxide can be

used in the EV battery cathode. Lithium for the cathode and electrolyte

materials is produced from lithium carbonate. In brine deposits, the

lithium chloride is concentrated by evaporating lithium-rich brines in

shallow pools from 12 to 18 months. It is then treated with sodium

carbonate (soda ash) to precipitate out the lithium carbonate.

Lithium carbonate can also be produced from clay deposits and spodumene, a silicate of lithium and aluminum.

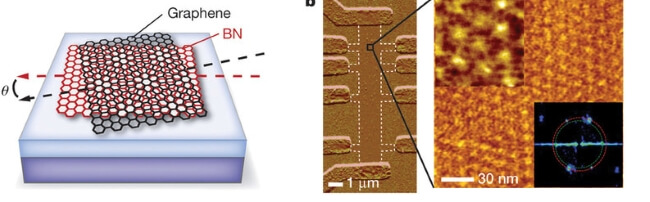

All lithium batteries contain some form of

lithium in the cathode and electrolyte materials. The battery anode is

generally graphite-based, containing no lithium.

Lithium carbonate derived from brine operations can be used directly to make lithium-ion batteries, but a hard-rock, spodumene concentrate needs to be further refined before it can be used in batteries, adding costs and complexity.

Despite being more expensive lithium

hydroxide is becoming more popular as a battery feedstock because it is

said to produce cathode material more efficiently and is necessary in

certain cathode combinations such as nickel-cobalt-aluminum (NCA) oxide

batteries and nickel-manganese-cobalt (NMC) oxide batteries.

About 75% of the 65,000 tonnes of lithium chemical production expected to come online this year is targeting lithium hydroxide.

While brine operations that suck up the

lithium in a salt-water solution and then evaporate it in large ponds

have historically been cheaper than hard-rock spodumene operations like

Greenbushes in Australia, that is beginning to change. A higher royalty

structure in Chile and a plant’s ability to make lithium hydroxide

directly from spodumene are two factors challenging this assumption.

But according to Benchmark, the case for

lithium hydroxide being the more competitive lithium-ion battery

feedstock is predicated on the battery market adopting high-nickel,

hydroxide-dependent cathode chemistries†(a proposition that looks

increasingly unlikely in the near-term) and secondly, that all spodumene

producers are integrated lithium chemical suppliers. So far none of the new lithium assets are owned by chemical converter companies:

The question in the lithium market is

no longer whether spodumene or brine resources will be developed – both

are needed to take us anywhere near the growth estimates of the next 2-3

years. The new questions is what other channels of supply will be

developed to take us close to the demand forecasts for 2025 and beyond.

Indeed if these new spodumene mines fail to

meet production costs, they will either cut output or close, which would

tighten the lithium market even further than expected. Already we are

seeing some spodumene producers in Australia balk at the prices they are

currently receiving, preferring to stockpile material instead.

Reuters reports, Converters

of hard rock lithium into battery chemicals in China were holding

around four months’ worth of stocks, or double usual levels… This has

slowed sales from overseas suppliers. Galaxy sold 44,630 tonnes in the

first half of 2019, against more than 90,000 tonnes a year earlier, at

an average price of $584, down from $940 a year ago.

If Australia’s spodumene producers are

priced out of the market, where would the lithium come from to meet

surging market demand?

The way things are going, it’s not likely to

be the United States. Despite having several properties at the

development stage, no new lithium mine has entered production on US soil

for over 50 years. The only producing mine is Albemarle’s Silver Peak

in Nevada – which has been going since the 1960s and is rumored to have

falling lithium brine concentrations.

China resource lock-up

We know from previous articles that China has been extremely active in acquiring ownership or part-ownership of foreign lithium mines and inking offtake agreements.

By 2025, the Chinese government wants EVs to represent 20% of all cars sold.

By comparison, the US sold 361,307 EVs in 2018, just under a third of China’s volume.

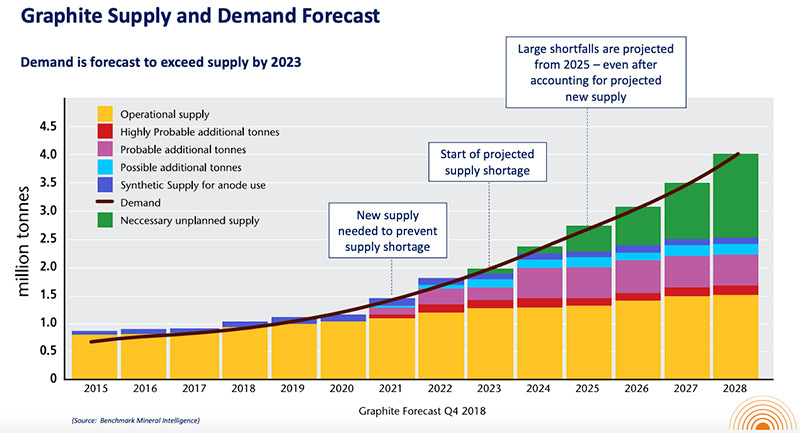

China of course, has also locked up the rare earths market and is the primary player in a number of critical mineral markets including cobalt, graphite, manganese and vanadium.

For years the United States and Canada

didn’t bother to explore for these minerals and build mines.

Globalization brought with it the mentality that all countries are free

traders, and friends. Dirty mining and processing? NIMBY. Let China do

it, let the DRC do it, let whoever do it.

China recognized opportunity knocking and

answered the door, seizing control of almost all REE processing and

magnet manufacturing, in the space of about 10 years.

Earlier this year, as part of its trade war strategy, China raised the prospect of restricting exports of these commodities, that are critical to America’s defense, energy electronics and auto sectors.

Over half of the world’s cobalt – a key ingredient of electric vehicle batteries –

is mined as a by-product of copper production in the Democratic

Republic of Congo (DRC). In a $9 billion joint venture with the DRC

government, China got the rights to the vast copper and cobalt resources

of the North Kivu in exchange for providing $6 billion worth of

infrastructure including roads, dams, hospitals, schools and railway

links.

China controls about 85% of global cobalt

supply, including an offtake agreement with Glencore, the largest

producer of the mineral, to sell cobalt hydroxide to Chinese chemicals

firm GEM. China Molybdenum is the largest shareholder in the major DRC

copper-cobalt mine Tenke Fungurume, which supplies cobalt to the Kokkola

refinery in Finland. China imports 98% of its cobalt from the DRC and

produces around half of the world’s refined cobalt.

In 2018 the United States produced just 500

tons of cobalt compared to 90,000t mined in the DRC. The US did not

produce any vanadium either; the top three producers of the steel

additive are, in order, China, Russia and South Africa.

As Quartz notes,

in order to maintain its dominance in the EV market, Chinese

manufacturers need a lot of cheap lithium. That explains why its largest

lithium miner, Tianqi Lithium, owns 51% of Australia’s Greenbushes

spodumene mine – the world’s dominant hard-rock lithium mine. And why

China bid for, and got, a 23.7% stake in Chilean state lithium miner SQM, the second largest in the world, for $4.1 billion.

China produces roughly two-thirds of the world’s lithium-ion batteries and controls most of its processing facilities.

Russia goes after lithium

This week the Uranium One Group, a

subsidiary of Rosatom, Russia’s state-owned nuclear company, signed a

deal with Wealth Minerals (TSX-V:WML) which has a lithium property in

northern Chile. The Vancouver-based junior sold 51% of its Atacama

lithium project to U1G.

It’s unclear what Uranium One – the same

company at the center of a scandal involving the Clintons – plans to do

with the 42,600-hectare property. WML would only say it’s interested in

partnering with U1G to “accelerate the development of lithium projects

by using modern technology and moving away from outdated solar

evaporation to a more efficient and environmentally friendly sorption

technology,†the company’s president, Tim McCutcheon, remarked in Monday’s news release.

We do know that Russia is paying more

attention to electric vehicles, despite petroleum being its number one

export by far. According to the Russian Ministry of Industry and Trade,

EV sales in the largest cities particularly Moscow and St. Petersburg,

grew 150% between 2017 and 2018, despite a 40% price increase.

The most popular model is the Nissan Leaf,

accounting for some 40% of all sales in 2018, followed by the

Mitsubishi i-MiEV and the Tesla Model S. Minister of Energy Alexander

Novak reportedly said that EVs should represent 8-10% of Russia’s total

car fleet by 2025- which would be a huge increase from the 10,000-11,000

EVs estimated to be on Russian roads at the end of 2018, Automotive Fleet reported earlier this year.

It’s certainly curious, if not alarming,

that Russia is already locking up lithium supplies, even though its EV

penetration rate is paltry compared to the top electric vehicle use

countries. Canada for example has about eight times more.

We can’t help but notice Uranium One is

doing the same thing with lithium, that it has done with uranium – be

the Russian government’s Trojan horse in dominating the world’s uranium supply.

Is it possible that Russia wants to be a

price-setter of lithium too, which even in oil and gas-soaked Russia is

likely to be a major new growth industry? It’s easy to see offtakes

developing between Russia and South American lithium brines, or maybe

Russia partnering with Chinese companies as they have done in the energy

sphere, as the country ramps up production of lithium batteries and

electric vehicles.

A run through the latest uranium mine

closures reveals the strong likelihood that Russia, through its

Kazakhstan proxy, aims to seek and destroy any threats to its dominance.

Besides Cameco’s mine shutdowns and US uranium production controlled by

Americans reduced to almost nil, other casualties of low U prices and

high-cost mining include French state-owned nuclear juggernaut Areva.

West Africa-focused Areva went bankrupt and had to be restructured into a

new company, Orano.

Australia’s Paladin Energy placed its Langer

Heinrich mine in Namibia on care and maintenance in May 2018, following

the mothballing of its Kayelekera mine in Malawi.

Rio Tinto’s Rossing uranium mine in Namibia

is an example of a high-cost mine that was carved up by the Russians and

handed over to the Chinese. The world’s longest-running open-pit

uranium mine, opened in 1976, produced the most uranium of any mine.

However, with production costs over $70 per pound, and the uranium price

still limping along at around $20/lb, it was only a matter of time

before too much red ink had spilled; in November 2018, Rio agreed to

sell its stake in Rossing to China National Uranium Corp.

With their low-cost production and

state-owned enterprises doing the mining and enriching, Russia,

Kazakhstan, and upcoming China can easily out-compete the private

uranium industry.

For example Uranium One, the Canadian

company that was swallowed up in 2013 by ARMZ, a subsidiary of Rosatom,

currently mines uranium in Kazakhstan, the world’s leading

uranium-producing country, at an average cash cost of $8 a pound.

In-situ mines operated by Uranium One and Kazatomprom dominated the

first two quartiles of uranium-mining costs in 2018.

In contrast Cameco, the third-biggest

uranium miner behind Kazakh

state-owned Kazatomprom and Orano (formerly Areva), reports its only

mine left after four closures, Cigar Lake, will be mined at $15-16/lb

over the remainder of its life.

Uranium One is vitally important not only to Kazakhstan’s uranium production, but Russia’s.

As a wholly-owned subsidiary of Rosatom, the

company is responsible for Rosatom’s entire uranium production outside

of Russia. That makes it the world’s fourth largest uranium producer.

Uranium One has part-ownership of six producing uranium mines in

Kazakhstan, the Willow Creek mine in Wyoming, and a 13.9% interest in a

uranium development project in Tanzania.

Russia and Kazakhstan have signed several nuclear cooperation agreements over the past decade or so.

The former Soviet satellite nation and

Russia currently account for over a third of US imported uranium,

effectively setting the price of the nuclear fuel.

US mine to battery to EV supply chain

The International Energy Agency is

predicting 24% growth in EVs every year until 2030. The global fleet is

expected to triple by 2020, from 3.7 million in 2017 to 13 million in

2020, according to the IEA.

Bloomberg forecasts there will be a 54-fold

increase in EVs between 2017 and 2040, when global light-duty EV sales

are expected to hit 60 million; there are currently about 4 million EVs

in the world.

Globally, battery makers and automobile

manufacturers are scrambling to ensure they have enough supply of the

silvery-white metal.

A Reuters analysis shows that automakers are planning on spending a combined $300 billion on electrification in the next decade.

Volkswagen has said it will invest $800 million to construct a new electric vehicle – likely an SUV – at its plant in Chattanooga plant, starting in 2022. For more read Volkswagen to drag Tesla, making EVs in Tennessee.

Opened in 2016, Tesla’s Gigafactory in Nevada is a going concern.

Every day 1,000 cars sets are trucked from the Gigafactory to an

assembly plant in Fremont, California. The three-storey structure, the

size of a dozen football fields, has 13,000 people working for Tesla and

its Japanese battery partner, Panasonic.

The company’s Model 3 was the best-selling electric vehicle in the US during

the first half of 2019. InsideEVs claims Tesla sold 67,650 Model 3s

through June, seven times the next best-selling electric vehicle,

Tesla’s Model X SUV. The Chevy Bolt and Nissan Leaf were also among the

top five best sellers.

GM is planning to sell its first EV this year, a 2020 Cadillac SUV, built in Spring Hill, Tennessee, in a move designed to challenge Tesla.

In 2017, coinciding with its 20th anniversary, Mercedez-Benz announced plans to set up an electric car production facility and battery plant at

its existing Tuscaloosa, Alabama plant. The $1-billion expansion will

include a new battery factory near the production site, with the goal of

providing batteries for a future electric SUV under the brand EQ. Six

sites are planned to produce Mercedes’ EQ electric-vehicle family

models, along with a network of eight battery plants.

Meanwhile more battery factories are being built, driven by the demand for lithium ion batteries which is forecast to grow at a CAGR of over 13% by 2023.

There are 68 lithium-ion battery

mega-factories already in the planning or construction stage. The first

phase of Tesla’s Chinese Gigafactory is reportedly almost complete; plans are also in the works for a Gigafactory in Europe.

Korean company SK Innovation has said it will invest US$1.6 billion in the first electric vehicle battery plant in the United States, and is considering plowing an additional $5 billion into the project, planned for Jackson County, Georgia.

All of this explosive growth in battery

plants and EVs will mean an unprecedented demand for the metals that go

into them. This includes lithium, cobalt, rare earths, graphite, nickel

and copper. Lithium for example is expected to see a 29X increase in

demand according to Bloomberg.

How will the United States obtain enough lithium for the electric-vehicle storm of demand that is brewing?

The US only produces 1% of global lithium

supply and 7% of refined lithium chemicals, versus China’s 51%. The

country is about 70% dependent on imported lithium.

To lessen US lithium dependency will require the building of a mine to battery to EV supply chain in North America.

The first step is to develop new North American lithium mines.

Lithium products from Albemarle’s Silver

Peak brine operation in Nevada are sent to its processing plant in North

Carolina. This material is then loaded on ships and sent to Chinese

battery manufacturers, which sell the batteries to automakers.

We don’t know how much lithium hydroxide

Albemarle exports from Kings Mountain (the company does not disclose the

amount to the USGS in tabulating global production statistics), but we

do not think it is significant in global terms. According to Visual Capitalist,

Silver Peak only produces 1,000 tonnes per year of lithium hydroxide,

within a current lithium market of roughly 280,000 tonnes per annum of

lithium carbonate equivalent (LCE), a term that encompasses both lithium

hydroxide and carbonate used in EV batteries.

Recently, oil-field services giant Schlumberger inked an earn-in agreement with Pure Energy Minerals that

could see Schlumberger – normally associated with oil and gas

operations – own a lithium brine project in Nevada. The company and its

subsidiaries have three years to acquire 100% ownership in return for

constructing a pilot plant for processing lithium brine.

Lithium Americas (TSX-V:LAC) is advancing

its Thacker Pass lithium project in Humboldt County, Nevada, about 100

km northwest of Winnemucca. In 2018 LAC completed a PFS that envisions

an open-pit mine that would produce 60,000 tonnes per annum of lithium

carbonate, for 46 years. The two-phase project, targeted for 2022, would

start with 30,000 tonnes per annum (tpa) then ramp up to 60,000 tpa.

The company recently said it has completed a Plan of Operation for

submission to the Bureau of Land Management (BLM), secured two partners

for mining engineering, and started a definitive feasibility study

(DFS).

Juniors: the next wave

Junior miners that have projects anywhere

close to production between now and 2040 are bound to do well in the

current lithium market, which as mentioned, is facing long-term supply

shortages, despite what you read about a glut.

Remember, supply would have to increase at a CAGR of 19% over the next six years to meet 2025 demand.

Albemarle’s Silver Peak mine is the only

producing lithium mine in the US, but there are other properties that

could become the next big producer. The old adage, “To find a mine look

around a mine†applies here. Below are five companies with US-focused

lithium projects under development. All are in Tesla’s home state

Nevada.

Ioneer (ASX:INR). Ioneer’s Rhyolite

Ridge project is a shallow lithium-boron deposit located 25 kilometers

from Albemarle’s Silver Peak mine. The company plans to leach lithium

and boron from the host rock using dilute sulfuric acid. The project

currently has a mineral resource of 4.1 million tonnes lithium carbonate

and 10.9Mt of boric acid. With the resource compiled from an estimated

20% of two prospective basins, Ioneer believes it can expand the

resource through further drilling. A prefeasibility study (PFS) was

completed in October 2018.

Cypress Development Corp (TSX-V:CYP). Cypress’

Clayton Valley Lithium Project, next to Albemarle’s Silver Peak lithium

mine, hosts a non-hectorite claystone indicated resource of 3.835

million tonnes LCE and an inferred resource of 5.126 million tonnes LCE.

A 2018 PEA showed a net present value of $1.45 billion at an 8%

discount rate, yielding an internal rate of return (after tax) of 32.7%.

Payback is just under three years. Cypress has successfully produced

lithium carbonate and lithium hydroxide that can be marketed to end

users, like electric vehicle battery manufacturers. Metallurgical

testing shows 83% lithium recovery. A Pre-feasibility Study (PFS) is

expected in October 2019.

Noram Ventures (TSX-V:NRM). The

perimeter of Noram’s claims are located within two kilometers of

Albemarle lithium brine operations. A technical report on the Zeus claim

block was updated earlier this year, the result of three phases of

drilling encompassing 60 drill holes. The new report identified an

inferred mineral resource of 1.5 million tonnes of lithium carbonate

equivalent (LCE).

Nevada Energy Metals (TSX-V:BFF). Nevada

Energy Metals acquired its BFF-1 lithium project based on descriptions

of geological modeling and historical drill results. The 2008 report

concluded that shallow thermal-gradient drilling and exploration by

previous operators demonstrated that this particular part of the Clayton

Valley contained the valley’s highest subsurface temperatures. The

company has two other lithium properties in Nevada, Teels Marsh West

located 77 km northwest of the Silver Peak mine, and Black Rock Desert,

which it optioned to LiCo Energy Metals in 2016.

LiCo Energy Metals (TSX-V:LIC). LiCo Energy

Metals is advancing the Black Rock Desert project it acquired from

Nevada Energy Metals. Under the option agreement, LIC can earn a 70%

interest in the project, and a 3% net smelter return royalty, by

spending $1,250,000 in exploration within three years. A soil sampling

program of 88 samples returned 73 samples containing over 100 ppm

lithium, with maximum values up to 520 ppm Li.

Conclusion

This brief survey of lithium juniors

operating in the United States shows there is tons of potential for

building the foundation of a true mine to battery supply chain right

here in North America. Doing so would put an end to US import dependence

on foreign suppliers of lithium, needed to serve the burgeoning

electric vehicle industry; the shift that occurred in the US oil

industry, from net importer to net exporter, is analogous to what could,

and should, happen with lithium.

The only way to break this dependence is to

develop lithium mines in the US. And that spells opportunity for ahead

of the herd investors.

Consider – Bacanora Minerals Sonora clay

lithium project in Mexico attracted a buy-in from

China’s Ganfeng Lithium. A payment of £21,963,740 from Ganfeng in

exchange for a 29.99% equity interest and a 22.5% joint venture (JV)

investment, helped boost Bacanora’s share price by over 50% this year.

Battery and EV manufacturers in the United

States need to get out in front of the looming lithium supply shortage.

Buy secure mine supply now or pay the pipers, Russia and China, later.

Richard (Rick) Mills https://aheadoftheherd.com/Newsletter/2019/Building-Americas-mine-to-battery-to-EV-supply-chain