Sponsor: Affinity Metals (TSX-V: AFF) a Canadian mineral exploration company building a strong portfolio of mineral projects in North America. The Corporation’s flagship property is the Drill ready Regal Property near Revelstoke, BC. Recent sampling encountered bonanza grade silver, zinc, and lead with many samples reaching assay over-limits. Further assaying of over-limits has been initiated, results will be reported once received. Click Here for More Info

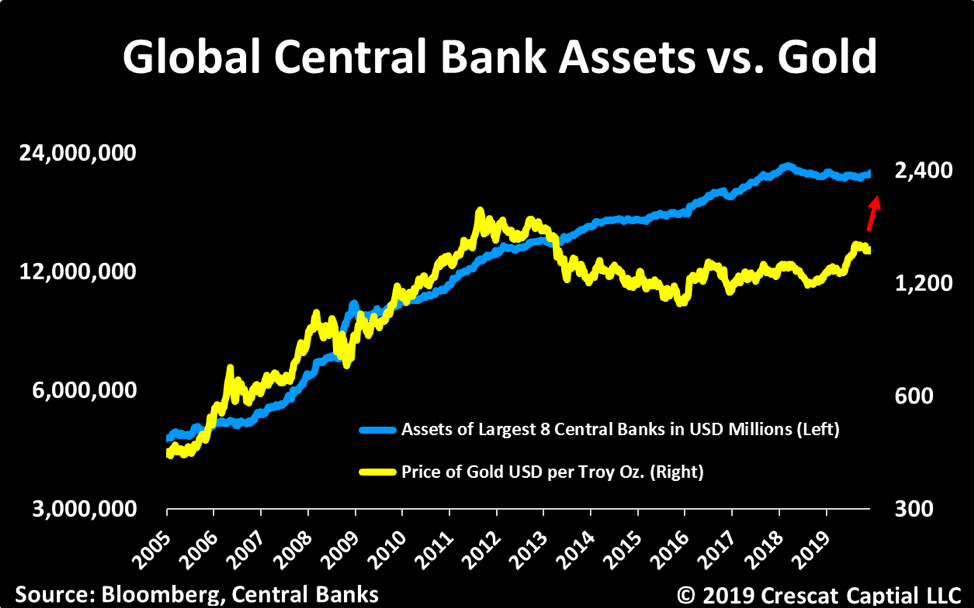

Central bankers have been voracious buyers of gold during the last two years, and analysts look for that trend to continue in 2020.

Through the end of October, net official-sector purchases this year

totaled 562 metric tons, reported Alistair Hewitt, director of market

intelligence with the World Gold Council. That 56.2-tons-a-month average

puts sales on pace to roughly match the 656 tons bought in 2018, which

were the most central-bank purchases since 1967, according to WGC data.

“This year has been exceptionally strong. We think that next year,

net buying will continue at a high level, even if it’s not as high as

this year,†said Philip Newman, director of the London-based consultancy

Metals Focus.

Goldman Sachs looks for global central banks to collectively acquire

around 650 tons in 2020, while Standard Chartered is projecting

central-bank purchases will total 525 tons.

“It’s still elevated,†said Suki Cooper, precious-metals analyst with

Standard Chartered. “That is still firmly on the buy side.â€

‘Safe, liquid and generates returns’

Hewitt commented that central banks are looking at three main

criteria when deciding to expand the amount of gold they hold within

their foreign-exchange reserves.

“For a central bank, gold is a fantastic asset because it’s safe, liquid and generates returns over the long term,†Hewitt said.

He also listed two more factors why the central-bank buying has suddenly jumped in recent years.

“One issue is we are seeing heightened geopolitical tensions,†Hewitt

said, with these involving major gold-buying countries and economies.

“Central banks are looking toward gold to balance some of that risk.

“We’ve also got negative rates and yields for a large number of sovereign bonds.â€

Newman added that many central banks are “trying to get away†from

the U.S. dollar. This is especially the case with Russia due to U.S.

sanctions, he added.

As recently as 2017, most of the official-sector buying came from a

handful of central banks, including Russia, Turkey and Kazakhstan. But

in 2018 and 2019, there have been a slew, including some that had not

been in the market for years.

“You’ve got a whole range of buyers,†Newman said.

The largest buyers during the first 10 months of the year were Turkey

with 144.8 tons; Russia, 139; Poland, 100; and China, 95.8.

Others include Kazakhstan, 26.9 tons; India, 17.7; Qatar, 11; Ecuador, 10.6; Serbia and the U.K., 9.9; Argentina, 7; Colombia, 6.1; Kyrgyz Republic, 3.2; Mongolia, 2.3; Belarus, 1.9; Guinea, 0.9; Egypt and Mauritania, 0.7; Albania and Malta, 0.6; and Ukraine and Greece, 0.3.

Goldman Sachs projected that central-bank purchases could amount to as much as 22% of global supplies during 2019.

Central banks ‘buy for an extended period’

Hewitt looks for official-sector buying momentum to continue.

Central banks tend to put a lot of thought into decisions to buy –

with a long, rigorous policy-making process — and purchase the metal

for strategic reasons, rather than simply reacting to day-to-day moves

in the price, Hewitt said.

“Once these people start buying, they continue to buy for an extended

period of time,†Hewitt said. For instance, he pointed out that

Kazakhstan has been a regular gold buyer since 2010.

“Both trade tensions and negative yields are still here,†Hewitt

said. “They may rear their ugly heads again and become more pronounced,

or they may fade away and become less pronounced. But those underlying

forces will remain ever present in the market. Certainly in the next

year or so, those two factors should continue to support and underpin

central-bank demand for gold.â€

Observers pointed out that not only have central-bank gold purchases

been strong, but sales have been light. Back in 1999, when European

central banks were selling the metal, they began following central-bank

sales agreements to try to limit how much was sold in any one year and

thereby keep this from being a destabilizing force in the gold market.

These agreements have been discontinued, Hewitt noted. Commerzbank

analysts pointed out they were no longer necessary since hardly any

European central banks are selling anyway. Germany’s central bank sells a

modest amount each year only for its coin-minting program, Hewitt said.

“The market was not bothered by the central-bank gold agreement

coming to an end, partly because the gold market is very different from

what it was in 1999,†Hewitt said, adding that there “dramatic sellingâ€

back then.

“The gold market today is just more diverse, more resilient and more

liquid. That’s why the market just shrugged its shoulder when the

central-bank gold agreement came to an end.â€

Further, analysts at Commerzbank, in their 2020 outlook, commented

that one or more Western European central banks might even enter the

market as a gold buyer.

“One possible candidate is the Dutch central bank (DNB), which in

October published a remarkable statement about the role of gold on its

website,†Commerzbank said. “In it, it described gold as an anchor of

trust for the financial system. According to the DNB, gold reserves

could serve as the basis for a new beginning in the event of a system

collapse.

“If one or more Western central banks indeed started to actively buy

gold, this would attract considerable attention and spark market

reactions.â€

SOURCE: https://www.kitco.com/news/2019-12-18/Central-banks-appetite-for-gold-expected-to-continue.html